One of the most well-known findings in the economic study of happiness is that, on average, happiness increases with income, but at a certain point diminishing returns set in.

In other words, money can only buy a fixed level of happiness, after which extra income and wealth don’t make much difference. Presumably, after this point, happiness depends on other things, such as health, leisure time, quality of friendships and close family.

Our new study, published in October, found the income level required to be happy in Australia has been increasing and moving out of reach of most Australians.

The happiness of increasing numbers of Australians has become more dependent on income than ever this millennium.

Happiness Increases With Income, to a Point

Nobel prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman first described the change point where extra income begins to matter less for happiness. He found this change point in the United States was US$75,000 in 2008.

This was substantially more than the US median income of $52,000 in the same year.

The difference revealed an unacknowledged inequity in the distribution of well-being in the US economy. The happiness of the poorest majority of the US population (68%) was tied to marginal changes in income, while that of a richer minority (32%) wasn’t.

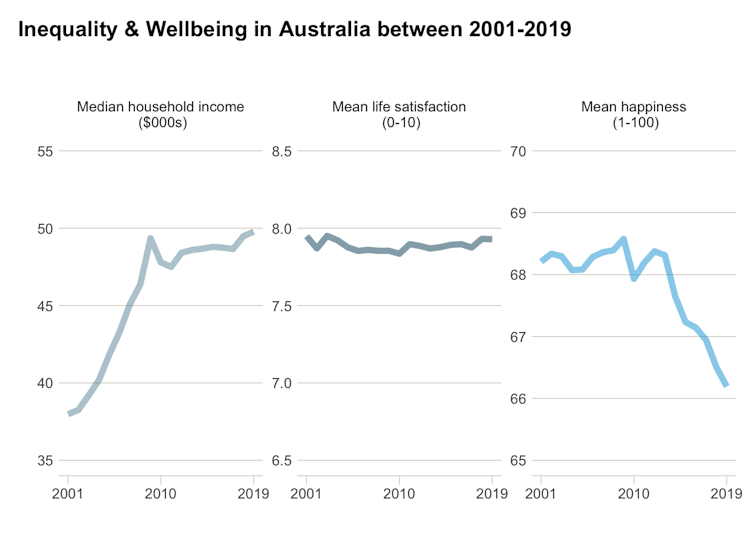

But what about fairer, more egalitarian countries with a strong middle-class, like Australia? Since the start of the millennium, Australia has enjoyed a growing household real income and stable levels of income inequality, better than the US and on par with the OECD average.

And the average level of life satisfaction in Australia has been reliably higher than the OECD average, as well as the US.

In terms of real income, income inequality and overall life satisfaction, Australia has a stable and solid record.

However, life satisfaction isn’t the same as happiness.

What Did We Study?

We used data from the influential Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey, provided by the Melbourne Institute.

This data show Australia’s average happiness has been declining since 2009.

The annual HILDA survey asks Australians to recall how often they felt happy, joyful, sad, tired or depressed in the last month, in each year since 2001.

The frequency of these feelings is quite different from a single rating of how satisfied you are with your life.

In our study, we combined each person’s frequencies into a single happiness score to see how it changed between 2001 and 2019 in relation to household income.

When people were asked to consider how often they experienced different emotions in the past month, rather than how satisfied they are with their life in general, the average happiness score peaked in 2009 and has declined every year since 2012.

What Did We Find?

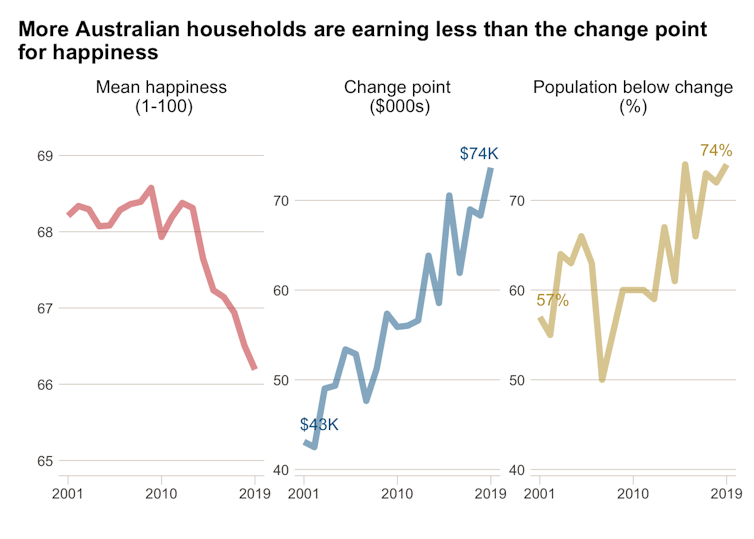

The change point at which the happiness of most Australians no longer strongly depends on income has almost doubled from A$43,000 to A$74,000.

At the same time, the median income has lingered at less than A$50,000 per year since 2009.

The number of Australians on an income below this change point has increased from around 60% to 74%.

These changes have taken place after adjusting for inflation and cost-of-living increases.

So What Does This Trend Over Time Mean?

Our work shows someone living in the average Australian household earning A$50,000 in 2001 and the equivalent amount in 2019 (adjusted for inflation) has become much less happy over the past two decades.

On the other hand, the happiness of people living in a wealthier household (for example, $80,000 per household) has been largely preserved.

Over the first two decades of this millennium, more and more Australians’ happiness has become dependent on their income, despite high life satisfaction ratings and stable income inequality across households.

These measures of economic well-being and equity, typically published by economic wonks and government policy-makers, aren’t revealing potentially important changes in the underlying marginal return on income across the Australian economy.

Income by itself doesn’t explain a large proportion of the variance in happiness, only around 5% (ranging between 1.6% to 14.8% in our study). But it’s still concerning because across the entire population these small changes can be expected to accumulate.

Australians’ happiness is becoming more sensitive to income as the change point has increased. At the same time, incomes are stagnating and happiness levels are declining, which is likely to drive further inequities in well-being between the rich and poor in Australia.

As Australia heads into a post-COVID world and deals with the economic after-effects of the pandemic, our government and its advisers need to pay attention to more than GDP and growth and ask whether the distribution of well-being and happiness is improving for everyone.![]()

Richard Morris is a Research scientist at the University of Sydney.

Nick Glozier is a Professor of Psychological Medicine, BMRI & Discipline of Psychiatry at the University of Sydney.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Read more stories from The Latch and subscribe to our email newsletter.