After enduring years of some of the wettest and coldest weather on record, Australians breathed a sigh of relief when La Niña finally ended. However, the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) has now officially declared that its warmer brother, El Niño, is underway.

Following months of speculation, with other international weather organisations calling El Nino already, the BoM is now confident that the Pacific Ocean is showing El Niño conditions.

“Oceanic indicators firmly exhibit an El Niño state,” the BOM wrote in a recent climate driver update.

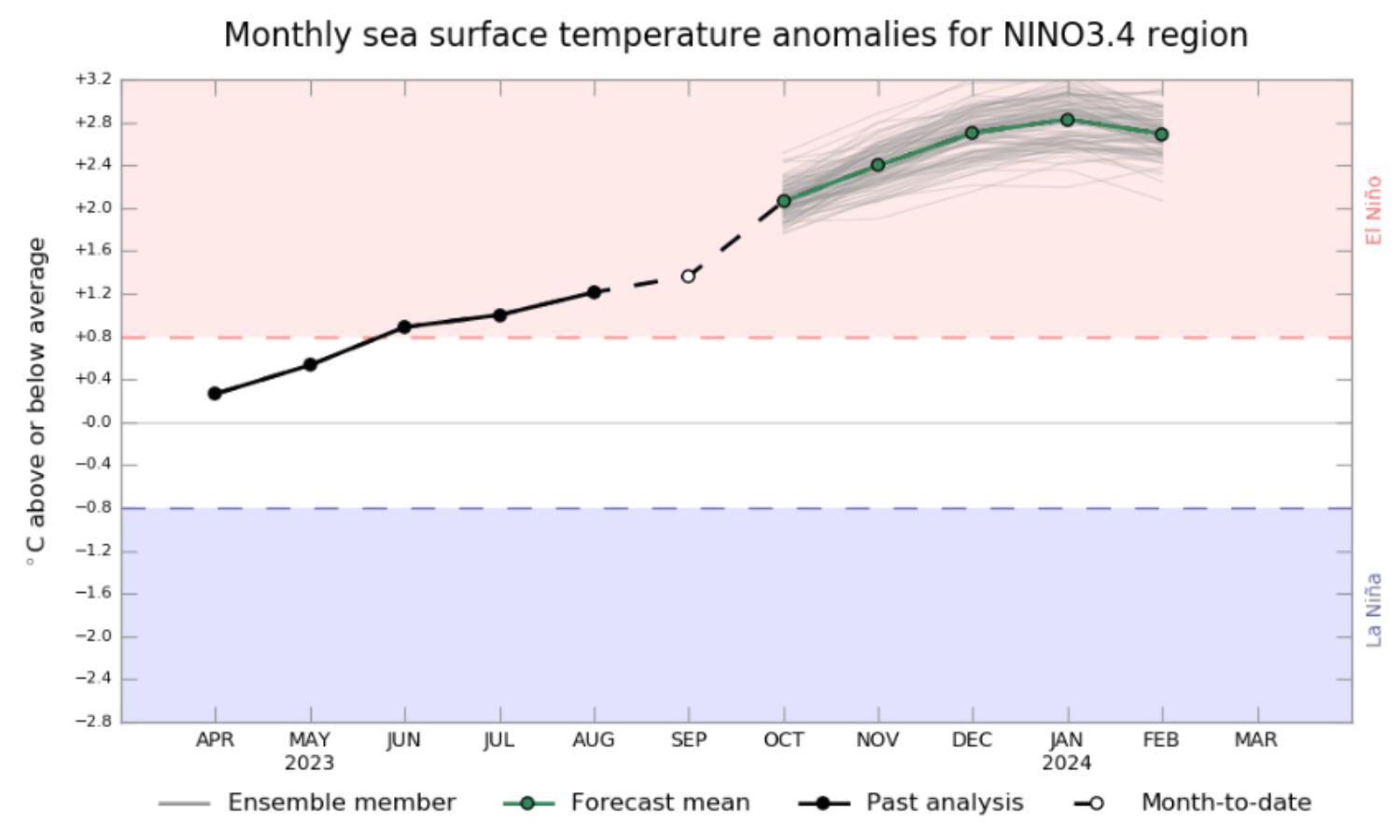

“Central and eastern Pacific sea surface temperatures (SSTs) continue to exceed El Niño thresholds. Models indicate further warming of the central to eastern Pacific is likely”.

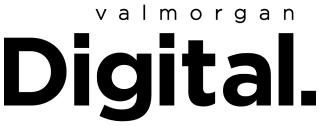

In addition, the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) has also shifted to positive. Together, both climate drivers will result in warmer and drier conditions over spring and summer for most of Australia, BoM Climate Manager Dr Karl Braganza has said.

“Over spring, their combined impact can increase the chance of below average rainfall over much of the continent and higher temperatures across the southern two-thirds of the country,” Braganza said in a press release.

“The Bureau’s three-month forecast for Australian rainfall and temperature have been indicating warm and dry conditions for some time.”

Average modelling of international forecasts for the coming summer show that we’re likely to be in El Niño conditions until at least February next year. The IOD is, however, likely to ease back to neutral by the end of summer.

The Bureau made the El Niño declaration after three of the four El Niño criteria were met, including a sustained response in the atmospheric circulation above the tropical Pacific.

The BOM is also forecasting that, by January, our ocean temperatures will be 2.8 degrees above average.

What Is El Nino?

El Niño is the opposite of La Niña. Whereas La Niña, as we’ve just experienced, means lower temperatures and higher than average rainfall, El Niño means higher temperatures and lower rainfall.

It’s a climate system in which warm water flows across the Pacific toward South America. This results in greater rainfall in the Americas but less rainfall here.

Both weather systems are abnormal and interrupt regular Pacific Ocean patterns. This results in fluctuations in nutrient levels in the ocean and subsequent fluctuations in fish and sea creature populations.

Much of Australia is already in a heatwave, with a mass of hot ear descending on Western Australia almost two weeks ago and slowly moving east. Temperatures are as much as 18 degrees above average in some parts of the country, smashing weather records. Experts have said this is a taste of what is to come this summer.

The Climate Council, who have given a briefing on El Niño, have said that the bushfire risk for Australia this summer could be catastrophic.

“We are in uncharted territory with El Niño,” Former NSW Fire and Rescue Commissioner Greg Mullins. “Decades ago, you couldn’t have a bad fire season without the intensifying effects of El Niño,” he continued.

Mullins explained that since 2009, the impact of El Nino hasn’t been necessary for a bad fire season. This time around, with an El Niño on the way and a lot of new growth around, he thinks we’re “set for a bad year.”

What Is a Positive IOD?

Like the El Niño-La Niña system, the Indian Ocean Dipole is a weather system affecting rain between Africa and northwestern Australia.

A positive IOD means temperatures are cooler in the eastern Indian Ocean and warmer in the west. This sucks moisture east towards Africa, creating less rainfall in Australia.

Bureau Senior Climatologist Catherine Ganter has said the Indian Ocean Dipole can have as large of an influence on Australia’s rainfall and temperature as El Niño.

“A positive IOD often results in below-average rainfall during spring for much of central and southern Australia and warmer than average maximum temperatures for the southern two-thirds of Australia,” Ms Ganter said.

As the BOM has repeatedly stated, climate change is currently exacerbating our weather systems. This means Australia, and the rest of the world, are increasingly subject to more intense and extreme weather events.

“Global SSTs were the warmest on record for the months of April and May, and the warmest on record for the Australian region during June,” the BOM state.

“The Australian continent has warmed by around 1.47 °C over the period 1910 to 2021. This is due to a combination of natural variability on decadal timescales and changes in large-scale circulation caused by an increase in greenhouse gas emissions”.

Related: Do You Have ‘Weather Fatigue’? You’re Not the Only One, But It Can Be Conquered

Related: Why the Weather Forecast Is Always Wrong Right Now

Read more stories from The Latch and subscribe to our email newsletter.